Run! A Stag Defends His Harem

Last October we spotted a herd of deer, both stags and hinds, in a field. It wasn’t long before another stag wandered in and decided to break up the party. After running around for a bit, the stag ran through the group of hinds and then walked away, trailing 3 of them!

Silk and Moss in the Kerry Woods

Everyone knows Torc Waterfall in Killarney, but O’Sullivan’s Cascade is a hidden gem at the other end of the Lakes of Killarney. There is a popular legend surrounding the cascade that it was once owned by Fionn MacCumhal and whiskey rather than water flowed from it. O’Sullivan of Tomies is said to have been the…

The Cliff Sitters at Clogher Strand

When we arrived at Clogher Strand for a photography session last month I spotted a group of teenagers sitting in the grass. I just realised something. They weren’t looking at their phones!

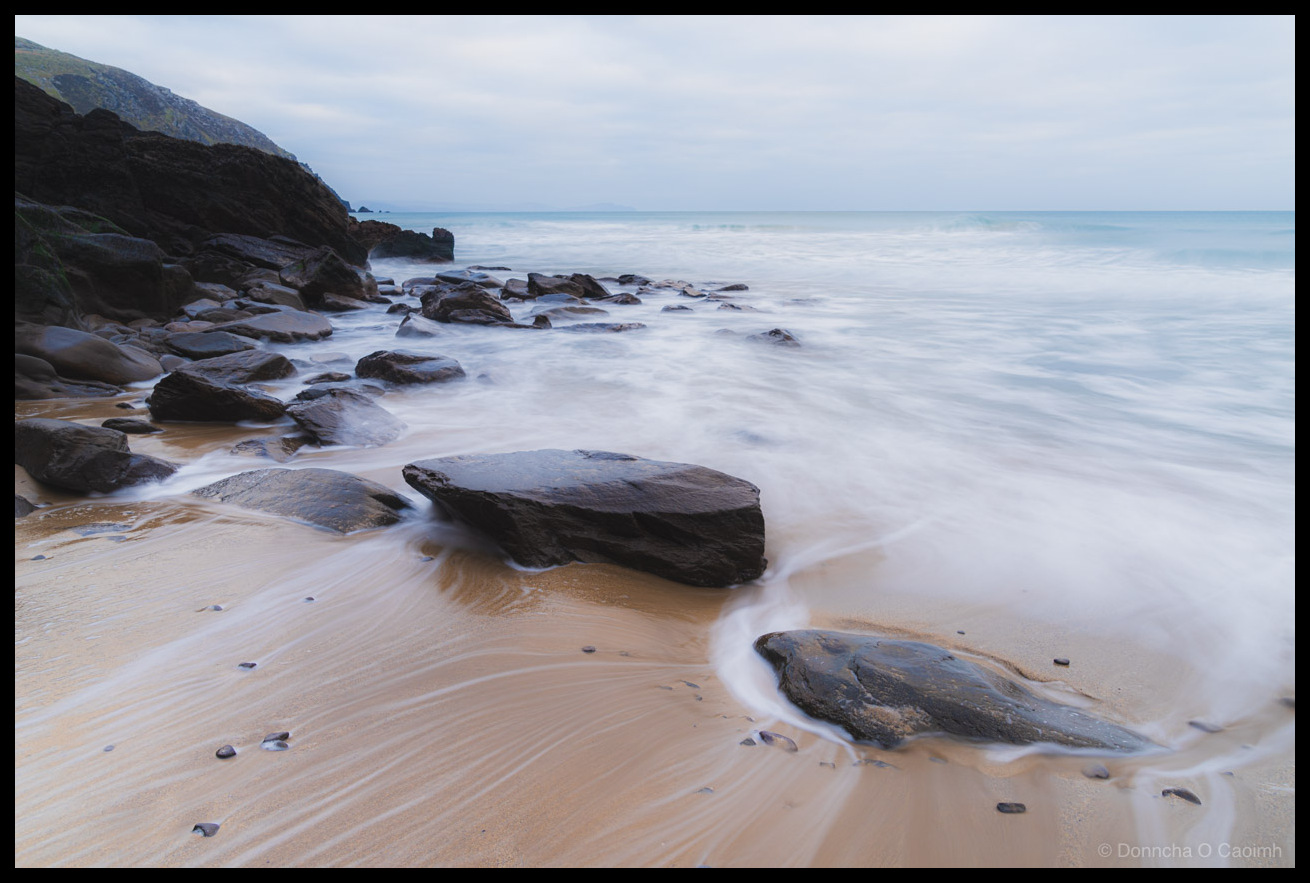

Long Exposure at Ireland’s Edge

The sea retreats in its forever battle with the sand. Clogher Strand in late December. The day was cold but we had fun.

Where Time Slows Down

Water becomes mist at Couminole/Coumeenole Beach on the Dingle Peninsula in Co Kerry.

Silk and Stone at Couminole

Waves crash on the rocks at Couminole, Co Kerry but are made misty by a long exposure photo.

The Dead Man Sleeps

An Fear Marbh as seen from the nearby Dingle Peninsula on a cold December afternoon.

Killarney’s Crystal Water

Last October when Blarney Photography Club visited Killarney to photograph the rutting season this year, we took a break from the deer and some of us went to O’Sullivan’s Cascade. This is the Lakes of Killarney as seen from where that waterfall flows into the lake. It was a beautiful clear day. The sky might…

Dingle’s Gentle Sentinel

Many years ago while travelling on the Dingle Peninsula we came across a donkey in a field in Muiríoch. I posted a photo of him in 2007 and again in 2008 but I happened to come across this photo of him and did a little work on the photo. There’s a chance this donkey is…

The Three Sisters at Twilight

The Three Sisters on the Dingle Peninsula in Co. Kerry. The sun had just sunk below the horizon and beyond a cloud bank at the horizon but the sky was still glowing a lovely soft yellow glow.

Killarney’s Red Deer Decoration

A stag digs up the grass to decorate his antlers in Killarney National Park a few weeks ago. Antler entanglement with vegetation is a common occurrence during the red deer rutting season and is primarily caused by a behaviour called “thrashing,” where stags violently shake their antlers against trees, shrubs, and ground vegetation. This behaviour…

A Killarney Stag’s Portrait

We were lucky to spot this stag and a number of hinds as we entered Killarney National Park a few weeks ago. The light was terrible. It was just after sunrise and we were walking through a wood. I’m thrilled with this photo of a magnificent stag. Here’s another photo of this stag.